THE ORIGIN OF THE IGBO

The vast majority of Igbo people inhabit the southeastern part of Nigeria with a few of them just west of the River Niger. A small number of Igbo-speaking people are also found along the southern coastline of Sierra Leone. Igbos are politically egalitarian and democratic. Speaking at the 1979 Ahajioku Lecture Series, Professor Michael Echeruo then of the English Department at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka and later the first Vice Chancellor of Imo State University suggested that “the Igbo are perhaps the only major ethnic group in West Africa which lacks the monolithic cohesiveness characteristic of a people with a long history of communal interaction.”

The ancestral origin of the Igbo remains largely speculative. One school of thought identifies Igbos from the general area of Onitsha, including Ika Igbos, with Benin ancestry. Some well-known families in Onitsha, however, reject this notion, tracing their ancestry instead to the Igala people of the Middle Belt of Nigeria. Yet another traditional folklore traces Igbos to the Ogoja and Ekoi people just northeast of Igboland. G.T. Basden, in his book The Igbos of Southern Nigeria, traces the origin of Igbos to the Jews, observing the great similarities in their respective cultural practices. Humphrey Eni of Ujari, in his book The Ujari People of Awka District (1965), argues that the Igbos of Arochukwu might have associated with, but not descended from, Jews expelled from Spain by Ferdinand and Isabella.

Whatever one’s persuasion in the continuing debate over the origin of Igbos, there is little disagreement that Igbos are generally ambitious, industrious, energetic, and unacquainted with idleness. “We’re all habituated to labor from our earliest years,” Equiano wrote, “competitive, progressive, and proud.” Inherent in Igbo tradition is the belief that a man is truly a man only if he can provide for and defend his family. Children, family, and community are the essence of Igbo traditional values.

The Igbo are a profoundly religious people who believe in a benevolent creator, usually known as Chukwu (The Almighty God) or Chineke (The God that creates), who created the visible universe (uwa). Opposing this force for good is agbara, meaning spirit or supernatural being. In some situations, people are referred to as agbara in describing an almost impossible feat performed by them. In a common phrase the Igbo people will say Bekee wu agbara. This means the white man is spirit. This is usually in amazement at the scientific inventions of the white man.

Apart from the natural level of the universe, they also believe that it exists on another level, that of the spiritual forces, the alusi. The alusi are minor deities, and are forces for blessing or destruction, depending on circumstances. They punish social offences and those who unwittingly infringe their privileges. The role of the diviner is to interpret the wishes of the alusi, and the role of the priest is to placate them with sacrifices. Either a priest is chosen through hereditary lineage or he is chosen by a particular god for his service, usually after passing through a number of mystical experiences. Each person also has a personalized providence, which comes from Chukwu, and returns to him at the time of death, a chi. This chi may be good or bad.

There is a strong Igbo belief that the spirits of one’s ancestors keep a constant watch over you. The living show appreciation for the dead and pray to them for future wellbeing. It is against tribal law to speak badly of a spirit. Those ancestors who lived well, died in socially approved ways, and were given correct burial rites, live in one of the worlds of the dead, which mirror the worlds of the living. They are periodically reincarnated among the living and are given the name ndichie the returners. Those who died bad deaths and lack correct burial rites cannot return to the world of the living, or enter that of the dead. They wander homeless, expressing their grief by causing harm among the living.

The funeral ceremonies and burials of the Igbo people are extremely complex, the most elaborate of all being the funeral of a chief. However, there are several kinds of deaths that are considered shameful, and in these circumstances no burial is provided at all. Women who die in labor, children who die before they have no teeth, those who commit suicide and those who die in the sacred month for these people their funeral ceremony consists of being thrown into a bush. Their religious beliefs also led the Igbo to kill those that might be considered shameful to the tribe. Single births were regarded as typically human, multiple births as typical of the animal world. So twins were regarded as less than humans and put to death (as were animals produced at single births). Children who were born with teeth (or whose upper teeth came first), babies born feet first, boys with only one testicle, and lepers, were all killed and their bodies thrown away in secrecy.

Religion was regarded with great seriousness, and this can be seen in their attitudes to sacrifices, which were not of the token kind. Religious taboos, especially those surrounding priests and titled men, involved a great deal of asceticism. The Igbo expected in their prayers and sacrifices, blessings such as long, healthy, and prosperous lives, and especially children, who were considered the greatest blessing of all. The desire to offer the most precious sacrifice of all led to human sacrifice slaves were often sacrificed at funerals in order to provide a retinue for the dead man in life to come. There was no shrine to Chukwu, nor were sacrifices made directly to him, but he was conceived as the ultimate receiver of all sacrifices made to the minor deities.

These minor deities claimed an enormous part of the daily lives of the people. The belief was that these gods could be manipulated in order to protect them and serve their interests. If the gods performed these duties, they were rewarded with the continuing faith of the tribe. Different regions of Igboland have varying versions of these minor deities. Below are some of the most common:

Ala the earth-goddess, the spirit of fertility (of man and the productivity of the land).

Igwe the sky-god. This god was not appealed to for rain however, that was the full-time profession of the rain-makers, Igbo tribesmen who were thought to be able to call and dismiss rain.

Imo miri the spirit of the river. The Igbo believe that a big river has a spiritual aspect; it is forbidden to fish in such deified rivers.

Mbatuku the spirit of wealth.

Agwo a spirit envious of others wealth, always in need of servitors.

Aha njuku or Ifejioku the yam spirit.

Ikoro the drum spirit.

Ekwu the hearth spirit, which is woman’s domestic spirit.

Theories of Igbo Origin

Many theory have been put forward about the origin of the Igbo people. Some claim that the Igbo migrated from the East and are either one of the lost tribes of Israel or Egypt. Another claim that they migrated from Western Africa. But available evidence such as Language diversity; Botanical (Forests Conservation); Population density; Archaeological, suggests that the Igbo and their forbears have lived in much their present homes from the dawn of human history.

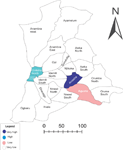

The traditional homeland of the lgbo people lies in the south-eastern region of Nigeria. They are situated between the great river Niger and Cross Rivers State, with the Ibibio, Ijaw, Igala, Idoma, Edo as their neighbors. The ancient settlement at Igbo-Ukwu in eastern Nigeria was an outpost for West African’s long-distance trade routes, one of which was the Trans-Saharan trade routes. The main items traded were gold, slaves, salt, cowry shells (the major unit of currency), weapons, expensive cloth, pepper, ivory, kola nuts, leather goods.

The arrival of Europeans on the coast of West Africa undermined the Saharan trade, but did not finally finish it until well into the 19th century. This also made the south-eastern region flourish, primarily trading slaves but after the abolition of slave trade in 1807, turned to trading in palm products, timber, elephant tusk and spices.

Igbo subgroups

The Igbos are a self-helping race who strongly believe in making themselves what they wish to be, hence the Igbo saying “Onye kwe Chi ya ekwe“. They are a people rich in culture and tradition. Although generally having very similar cultures, they also show a local variation in cultures and customs.

Based on these variations the Igbo land can be divided into five main subgroups:

1. The Northern Igbo:- Igbo-Ukwu, Onitsha, Enugu, Nri-Awka

2. The Western Igbo:- Ogwashi-Ukwu, Asaba, Agbor,

3. The Southern Igbo:- Umuahia, Ngwa, Owerrinta,

4. The Eastern Igbo :- Afikpo, Arochukwu-Ohiafia, Bende

5. The North-Eastern Igbo:- Ogu-Ukwu, Abakaliki

After several military conquests, Igbo land now came under British colonial rule. This was a style of government not very popular amongst the Igbos, hence the British were faced with a lot of protest and resistance, but Igbo land still became a British Colony.

In 1900 the area that was once administered by the British Niger Company now became the Protectorate of Southern Nigeria. Control of this area then got passed from the British Foreign Office to the Colonial Office. By 1900 - 1914 the Northern and Southern Nigeria were amalgamated. Then afterward the Eastern Region was formed and subsequently was divided into several other states.

Early Igbo Currency

Historically a variety of objects that have been used across Africa to facilitate trade and measure wealth. Although cowry shells, aggrey beads, ivory and cloth have served historically as currency, metals have also been used from the earliest times.

Some pre-coinage currencies used for goods and services include:

Cowry shells

Cowries money is one example of odd and curious early primitive money. Cowry shells of many varieties and species were the first universal currency. Igbos exchanged the polished, white and yellow, olive-sized shells imported from the Maldives Islands in the Indian Ocean. The earliest evidence of their use in Africa was found in the pre-dynastic tombs of Egypt (c. 4000-3200 BC). These shells were ancient money used, not just in Igboland, or in Africa, but throughout the world, predating the use of coins or in some instances used in the same economy as metal coins. In Igbo land they were a sign of wealth and importance and served for small everyday transactions and, gathered together in the millions, for bride wealth (a groom’s gift to the family of the bride) and other major purchases and gifts. The shells were believed to possess the power of fertility, thus ensuring their acceptance throughout the wide territories of Africa. Inflation and problems transportation eventually rendered the cowries impractical as thousands of tons of cowries had to be shipped to West Africa.

Bracelet

Bracelets, that were cast or hammered from copper had little circulation and were never used in connection with routine transactions. Instead, they served as reservoirs of wealth in a form that was easy to store and transport. This storage function is best illustrated in the very heavy bracelets of the South-Eastern Nigeria region. To create some of these bracelets, the artists poured molten metal directly into a cast in the ground called a puddle mold. As the metal cooled, it was wrapped into a circular shape and often even fitted directly to the wearer’s body. Representing stored family wealth; these ornaments were usually large and heavy and were worn by people of high status throughout Igboland. Aside from their intrinsic value, they were also valued for their artistry.

Manilla

Manilas entered the local economies as a form of currency and were a highly profitable item of trade. They circulated West Africa from the end of the 15th century to 1948. They were originally made of copper or brass and later composed of a mixture of other metals. Copper and brass manilas were heavy open bracelets shaped like house shoes, with bulbous ends. The quality of their ringing sound and the amount of “flash,” or excess metal extruded at the joints of the mold, helped determine their value. The small manilas with flared ends were manufactured in Birmingham, England, for export to Africa. Larger examples, called king, queen or prince manilas, were status symbols and more a store of value than currency. The queen manila shown here was worth about 75 small ones. During the mid-1500, Portuguese seamen were reported to have paid about 50 manilas for an ounce of gold.

Early Igbo Writing

Nsibidi

Before the colonization of Nigeria by the Europeans, the Igbos and their Efik, Ibibio and Annang neighbors developed a system of writing known as Nsibidi The Nsibidi style of writing is independent of any external influence, has been in existence in South Eastern Nigeria since 1700 and does not rely on Arabic or Latin script. It is based entirely on signs and symbols. The exact origin is not certain but some investigation indicate that the writings originated among the Ibibios and, through trade and other social & economic communication, became adopted and better developed by their Igbo neighbors.

One of the first European to discover the existence of Nsibidi was Mr. T. D. Maxwell, in 1904 and a year later he displayed 24 Nsibidi signs at a native goods exhibition which was later published

Nsibidi scripts can be seen on tombstones, secret society buildings, costumes, ritual fans, headdresses, textiles, and in gestures, body and ground painting. They are also used for religious rituals and cultural celebrations, recording court-cases, messages and secret societies records, proverbs and short stories and for writing private love letters.

One of the reasons Nsibidi became obsolete may have been due to the fact that it was surrounded in a great deal of secrecy. It is known that the use of writings was popular among secret societies like Mmanwu, Ekpe and Okonko. It appeared that writing Nsibidi required formal education, which emerged to be available for those seeking to enter a secret society.

Nsibidi scripts have been discovered in use in some Afro-religious rituals in countries like Haiti and Cuba.

Adapted from Ekwenche: http://nzukoigbobrescia.tripod.com/ohazurume/id1.html